Multi-fly Rigs

One good, two better, three best

My father was a great fisher of wet flies. He started me fishing at a tender age. He’d make a cast and hand me the rod and I’d let the flies swing across the stream. The rig always consisted of a pair of wet flies. My two favorite combinations were the Invicta and the Coachman or the Teal and Green and the Watson’s Fancy. They caught trout. A lot of trout. And they still do. Fishing a pair of wet flies was how I grew up. So fishing more than one fly on the leader was just something I always did. It wasn’t until I got to college and started fishing with people other than my Dad that I realized that a multi-fly rig was the exception rather than the rule. In the years since then it has become more common, but still not as common as one might think.

The absolute acme of fishing multi-fly rigs are the streams and rivers of the Rocky Mountains. Several decades ago I fished the Eagle River in Colorado for the very first time. It was late June and the runoff was on the way down. This was not the beautiful caddis heaven of the post runoff season.

The water was rushing down the river in a mostly unfishable torrent, however, there were soft cushions along the edges where the fish could hold and feed. But you had to get their attention fast because the raft we were in went drifting by in a hurry. A sort of fly fishing drive by.

The guide, once again my buddy Kevin Wildgen, looks through my boat bag and pulls out two heavy wooly buggers, one white and the other black. He say tie those on. I said, “Which one?” He says, “Both, about a foot or so apart.”

Me: “Two woolly buggers, that’s crazy." Kevin: "I know guys who fish three." Me: "Okay, then."

Took a little getting used to but I caught a bunch of fish. Thirty years or so later, it’s June 2025. The Mid Atlantic has been getting rain by the bucketful. Streams we should be fishing the tail end of the spring hatches look like they’re in runoff. Even little woodland streams

I’m standing by one of them trying to figure out what to do and I remember the Eagle. But I’m all sophisticated now - I fish tube flies and MOW tips and such. Well no time like the present to try it on a little Mid Atlantic stream.

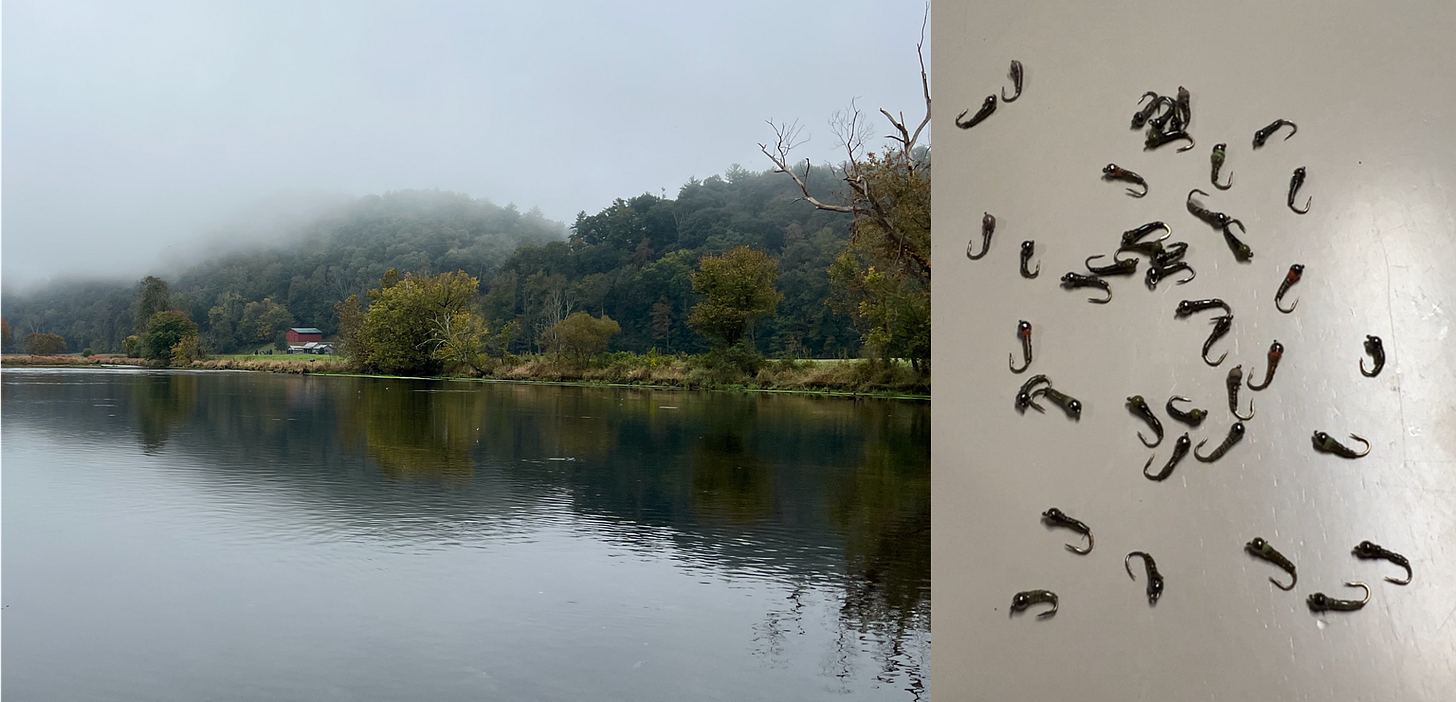

That water is crystal clear, but it’s also a healthy waist deep and moving along. So I tie on two copper tube flies and stick on a 10 ft. T8 MOW tip. And I started catching fish, first one, then another and so on. Here’s what two streamers look like swinging by (expand the videos to get a better look).

Once you see it, you can also see why the concept works. Look at a bunch of fry or minnows and you’ll see how they move in choreographed synchronicity. a pair of streamers does just that. Plus the ability to present two different flies doubles your chances of getting a fishes attention.

A dry dropper rig is now pretty standard everywhere in the US. And the obvious reason is that you can present the fly to fish in two ways and hope to get a take regardless of where that fishes attention might be. But actually there’s a hidden message in that reasoning, and one that most people seem to gloss over. Why is it that you can offer a fly on the surface, and one or more below the surface and expect to get a take? The answer actually lies in something I’ve mentioned in a number of articles on this site - trout are essentially opportunistic feeders and will grab whatever’s at hand, unless their attention is being drawn by an overwhelming numbers of one item. And because of this the selection of the dry fly (and the subsurface flies) is critical. Not only must this fly hold up the subsurface stuff, but it must also grab the occasional trout’s attention. If it doesn’t do that you’re better off fishing an indicator. They’re easier to deal with. Here are two wild rainbows taken in one of my local rivers on a cold November 25, one at about 4 PM and the other a half hour later. One took the dry and the other one of the droppers. The water temperature was in the mid to upper 40s. Given the right incentive the fish will rise.

The selection of the dry fly uses the same rules I discussed in my long series on dry flies (particularly the bit about attractors.

The Dry Fly Patterns -1. Attractors

There was a Persian poet, Amir Khusrau who upon seeing the beauties of Kashmir supposedly said , “If there is heaven on Earth, it is here.” (And may be I’ll write about trout fishing in Kashmir one day, because it truly used to be spectacular, and hopefully still is). But I’d take exception with Mr Khusrau’s claim. If there is heaven on Earth it is bet…

My personal favorite in this category is the LaFontaine Double Wing, but anything you’re confident in will probably work. I’ve also had good luck with caddis patterns or under certain conditions (like during a hatch) with other patterns.

The craziest extension of the dry dropper thing I’ve ever come across, and in the passing used very successfully, was hanging a small midge pupa under a small Griffith Gnat (about a size 20-22). This was taught to me by by friend Matt Murphy, a guide of many and hidden qualities. On cool mornings, under a clouded sky, when they aren’t releasing water on some tailwaters, the fish will pock the glassy surface of glides taking midges. We get a lot of takes on a pupa hung about 6 inches below the Griffith’s gnat.

I even sink a bunch of subsurface flies under caddis flies or imitations of mayflies that hatch sporadically. The Stenonema Vicarium lot comes to mind (That’s the March Brown and Gray Fox - yes they’re the same species). Those flies hatch sporadically throughout the day and when they float over a trout, in a spot where the trout can take one, it often will. But the fish never get keyed onto them and hanging subsurface stuff below them will offer something to the fish that’s down there.

The dry dropper technique works best where you can sink relatively lightly weighted flies down quickly. On bigger rivers wide, shallow riffles are an ideal area, as are the buffer zones along the bank and the first drop.

Certain types of small streams, especially those with shallower, wider sections also provide ideal water for dry dropper fishing.

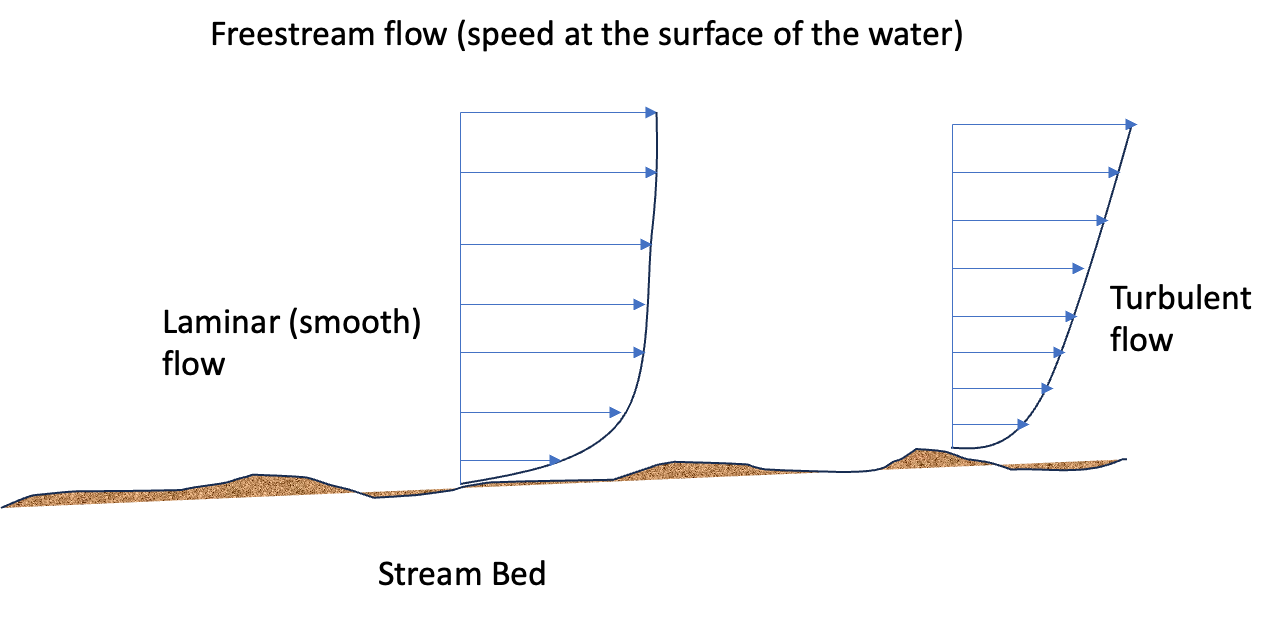

There’s a delicate balance in the world of dry dropper fishing. One has to remember that dry flies can’t suspend a set of nymphs the way an indicator would. At the same time it doesn’t mean that a dry fly can’t be used in a dry dropper rig with weighted flies or even a weight on the leader. The real balance lies in being able to keep your flies all moving along at about the same pace. While it needs a bit of work, this is not difficult once you get understand what’s going on and the hang of the line control needed. I can keep a dry with 3 droppers below it drifting for hundreds of feet from a drift boat (at my age that’s no longer a boast, merely a statement of fact). Here’s what you have to understand. The speed at the surface is often faster than what it is where your nymphs or wets are floating.

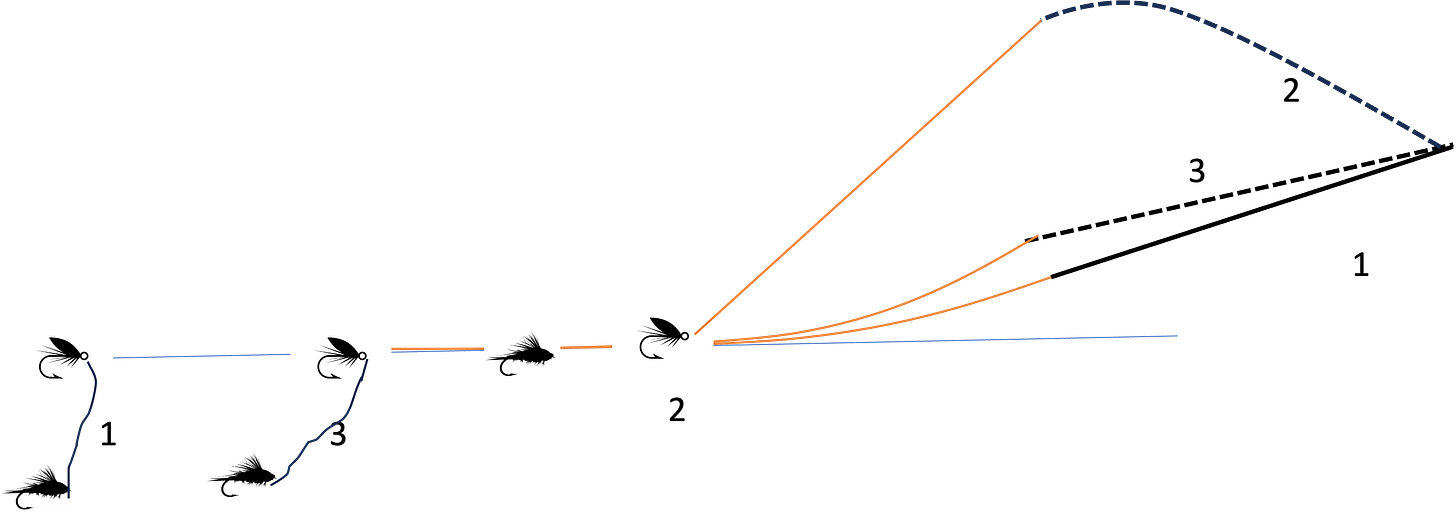

The first thing you want to do is give the wets a head start on their way to the bottom. It’s a bit different if you’re casting upstream as you may when wading or down and across as you would under certain wading conditions or from a drift boat.

Let’s tackle the upstream condition first. If you’re a fancy caster you can make a tuck cast and buy yourself a split seconds worth of extra sink time. Most of the times it isn’t worth the effort. What is worth the effort though is a quick upstream stack mend as soon as the wets starts sinking. Throw a little loop like a roll cast that flicks your dry upstream of the wets. Now as the flies start sinking the dry throws a little slack into the leader allowing it to sink deeper. As the flies drift down repeat that stack mend at intervals allowing the dry to slow down to keep pace with the sunken flies. Here’s a video of what a stack mend involves. This lad being substantially younger and brawnier than I am is using his whole being to make that mend. Use a long (10 ft) fast rod so it doesn’t collapse and a quick roll cast is all you need.

A good roll cast does the job. With a little practice (like 5 minutes on the stream) you’ll be able to just flick the dry upstream. The sunken flies act like anchors. When you’re casting down or across start off by making your wet flies land downstream of the dry. If this is difficult, don’t worry. Use your rod tip to lift the line and leader up and let the wets trail down below the dry. Now drop the rod tip down, shake out a little slack and you’re off to the races.

Now as the flies drift downstream, mend any unseemly bulges out of your line and occasionally repeat the repeat the lift and drop back of the dry. With a little practice you’ll be able to move just the dry without pulling the wets up.

There is another delicate balance one needs when fishing dry dropper rigs. You want your total dropper length to be not more than about 1.5x the depth of the water you’re fishing. If the dropper gets too long your dry fly will be far removed from the wets and drift control and bite detection becomes difficult. And since you are fishing nymphs or other sinking flies you do want your bottom fly to be close to the bottom, which is where most fish lie. In order to do that you need to sink your flies well, but you can’t afford to sling a bunch of lead around. The best way I’ve found to do this is to use what I call the “maggot rig.” I talked about this in an earlier article.

Nymph Rigs

Nymphs, or other underwater flies imitating creepy, crawly, drifty things probably account for more fish than any other form of fly fishing unless you’re a diehard streamer or dry fly fisherman. And I’ll address the dry fly part in another post. One thing at the butt of all sorts of arguments is how to actually construct a rig to fish you nymphs. Everyo…

The difference here is that we aren’t fishing very deep. So I would forgo the splitshot and just use a bunch of beadhead nymphs. I don’t personally bother with brass beads. Just go with the tungsten ones. Yes they might cost a tad bit more, but would you pay a dime to catch a 20-inch trout? The question answers itself. The Maggot Rig necessitates the use of two or three flies in order to get your rig correct. Do check the regulations where you’re fishing to see how many flies you can actually use. If I can I normally fish what my friend call a dry-dropper-dropper-dropper. Except in Tennessee where I have to fish a dry-shot-dropper-dropper because they limit you to 3 flies. Yes the three flies offer themselves at different depths, and that’s a good thing given the poor eyesight trout have. But most importantly they get the business fly down to the strike zone.

There is one multi-fly rig that there ought to be a law against. It is, in my opinion, unconstitutional, and should be deemed immoral, illegal, fattening, and everything undesirable. It’s this abomination some guides use called the hopper-dropper. It’s the lazy man’s way out of trying to coach your sports into doing the right thing. I know this is one man’s opinion, but this time I also know I’m right. The best dropper fishing is always to be had by plonking your hopper down with a splat close to the shore. Find the deeper drop offs next to shoreline vegetation and pound them with a hopper.

Twitch that hopper, make it move and drift and skitter and drift and lift it up an plop it down again. You need to get the trout’s attention. You can’t do any of that when you have a couple of droppers hanging below your hopper. If you’re fishing it right the droppers will end up on the shore. They’ll be zipping around all over the place when you twitch the fly, and they act as parachutes that hamper that delicious little plop. Yes you’ll catch the occasional fish on the dropper and some fish might even come up and eat that hopper. But good hopper fishing, when the warm summer wind gets them crackling and they whirl out of the vegetation like dervishes to often crash along the edge of the stream paddling away like crazy shouldn’t be a sport for occasional trout. This is where the bad part of hooking a trout is that it keeps you from dropping your fly down on the next hot spot. So, don’t do that hopper-dropper thing. It isn’t good for you health, wealth or well being.

October and November Mornings in the Colorado valley always start off brisk and chilly. Up on the mountain where we live the mornings are in the 20s. The lack of moisture makes them bearable. Move down the valley from the mountains and the temperature starts going up a bit. Of course there could always be the odd snowfall.

The flows are lower and gentler. This is the time of the fall Blue Winged Olive and midge hatches. The flies often come off at the same time. The trout line up along the seams and suds lines, in the back eddies and feed voraciously. Hook jawed post spawn brown,

chunky rainbows,

cutthroats and and cuttbows, all fattening up for the coming winter.

They rise in pods, hovering right below the surface with a sight window that’s about 4 inches across. And they tend to get keyed in on the insects drifting by them. In these mixed hatches you’ll notice that there is a seeming segregation in the drift lines. The BWOs are drifting down one line and the midges down another. One fish takes the midge pattern readily, and the other the BWO. But it’s often hard to see which is which.

We see the same thing on summer evenings when the PMD spinners are coming down and so are the caddis. Small changes in lies can make one fish take one and the other one the other fly. Unless you see which one the fish is taking it’s often hard to figure out which one to throw.

So throw them both. As the say, “Ain’t nothing but a thing.” Tie on a spinner and a caddis, or a BWO and a midge. Present them in turn or simultaneously. Present one to one fish, the other to a different one in the same pod. Heck use one to allow tou to see the other. It works. Two dry flies on the leader is a concept dear to my heart. I don’t think I’ve fished a single dry fly in more than thirty years. (It’s been bugging me so I had to come make this edit - when I say I don’t ever fish a single dry fly it’s with one exception - when I’m fishing a hopper. Then I do fish a single fly because fishing two hoppers is akin to putting pineapple on pizza - there are some things that are just against the laws of man, God and nature).

Drift down this section of the best trout river in my world. Cast an ant and a beetle under and around that overhanging vegetation.

If the thunder won’t get you then the lightning will.

Sometimes they both do.

What a great article. Have fished drys and droppers many times on western rivers but never 2 drys at a time. Got to try that! Especially the PMD/caddis combo at dusk. Oh yeah. Thanks for the ideas.