The Dry Fly Patterns -1. Attractors

The flies that bring fish to the surface when there is no hatch. Part 5 of N

There was a Persian poet, Amir Khusrau who upon seeing the beauties of Kashmir supposedly said , “If there is heaven on Earth, it is here.” (And may be I’ll write about trout fishing in Kashmir one day, because it truly used to be spectacular, and hopefully still is). But I’d take exception with Mr Khusrau’s claim. If there is heaven on Earth it is between here

and here

on a summer evening with all your rods rigged with dry flies, a good friend at the oars, the casting arm limbered up and the fish ready to rise. This is the dry fly capital of the world, where trout rise with abandon to anything you can throw at them, as long as you throw it to the right place, at the right time. It’s attractor dry fly fishing at it’s best. But our attractors aren’t any of those other colorful and large things. They’re simply size 14 and 16 caddis flies, or a generic mayfly imitation. Sometimes I go wild and crazy and put one of each on the leader, other times I just stick to the caddis. Caddis adults make great attractors.

So great that I tie them by the seeming bucketful. In my way of thinking if there’s no hatch, and no regularly rising fish, then whatever you raise them on is an attractor pattern. Some of these flies may be designed for the specific purpose of attracting the fish’s attention. Gary LaFontaine’s Double Wing is an elaborate attractor. Created by accident, but enshrining a lot of properties of a good attractor.

Here’s a spread of part of my collection of LaFontaine’s masterpiece, the Double Wing. These are the size 10s and 12s. I tie them down to 16s and some 18s.

However, an attractor doesn’t have to be anywhere near that elaborate. The caddis above are great attractors. The Adams is a general purpose, all round attractor dry fly - a sort of floating pheasant tail.

The key to an attractor pattern is that it brings up trout when there is no apparent surface activity. Attractor fishing with dry flies can be immensely productive under the correct conditions. There are many days where the only fish I see rising are he ones rising to my fly. But they do rise to my fly with amazing alacrity.

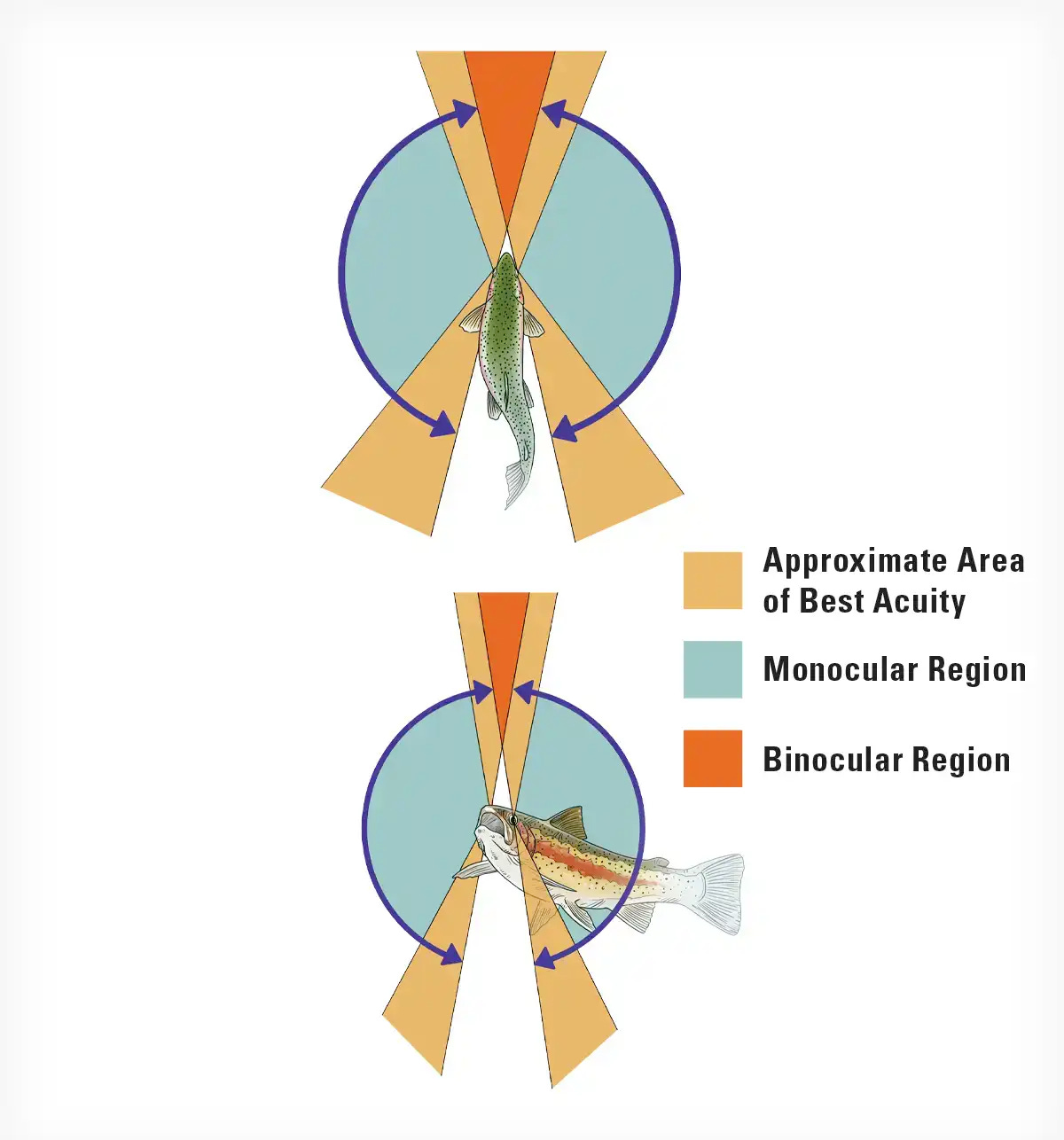

Unless there’s a hatch going on, or some sort of massed drift - behavioral or catastrophic, trout are by circumstance opportunity feeders. A trout’s vision is three-dimensional, there’s an azimuth and an elevation components at all times. Our vision is mainly pointed to the front with a fairly wide view from side to side and a narrow view top to bottom. But we have large blind zones.

A trout’s vision on the other hand has very small blind zones, and because of its monocular vision very wide coverage on both sides.

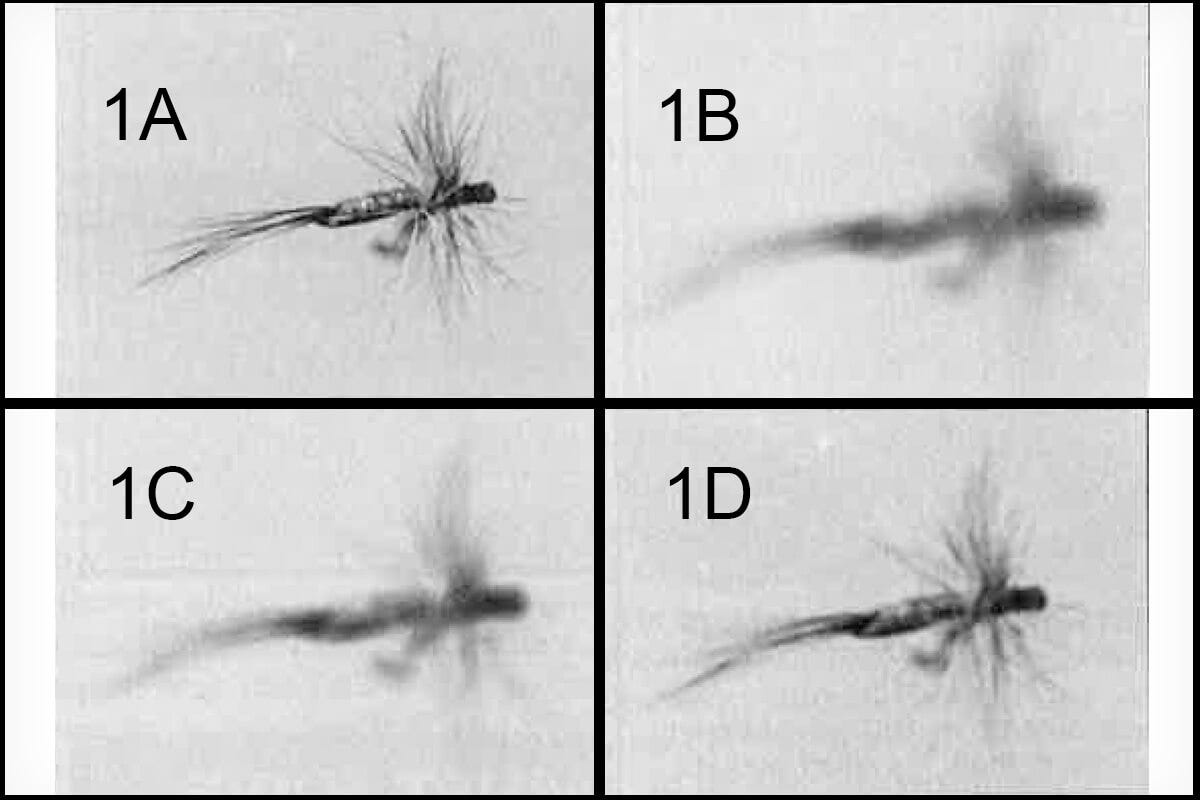

What that means is that trout are looking for food over about 330 degrees in elevation and 330 degrees in azimuth. But a trout’s vision lacks very severely in acuity. It just doesn’t see very well. It’s a bit like a shortsighted human without their glasses. They see color and forms and such but not the specifics. In fact a trout looking at a fly at any distance sees a sort of blur. This picture shows a human’s view of a fly from a foot (1A) and a trout seeing the same fly from 1ft (1B), 6 inches (1C) and 3 inches (1D).

And this is why flies use wholly unnatural artifacts to catch fish. The tinsel and metallic ribs used on nymphs are entirely unreal. A nymph like the Prince totally lacks in verisimilitude. A fly often used out West is a thing called the Lightning Bug, which might just have been the precursor of the Rainbow Warrior, except they tie it in sizes up to a 12.

Flies like this work by catching the trout’s attention. If you have trout lying in a spot where it’s relatively easy for them to rise a fly that catches their attention on the surface will have the exact same effect. We’ve all seen trout rise at random, to some utterly random bug floating down the river. Why wouldn’t they rise to a fly you’ve presented to them?

The answer is they will, at all times of the year. You just have to throw the right thing to them. Here are two fish, a wild brown and a wild rainbow, taken about 3 days apart on November 29 and December 2 about 100 miles apart, both on the exact same dry fly. Both were taken in mid sized rivers on relatively cold days.

Drawing a fish’s attention with a dry fly can sometimes be easier than it is with a nymph or other larval imitation. Once you’re into the late summer, fall and winter the size of mayfly nymphs and caddis larva present in streams goes down dramatically. Unlike things like stoneflies, these other insects, which often form a large percentage of subsurface life have a yearly life cycle. Which means after the spring and summer hatches we’re looking at aquatic macro invertebrates that may still be relatively small. Of course streams that have healthy populations of scuds and sow bugs can offset these insect populations, but only to a the extent that they exist in that stream. The reduced flows in fall and winter also lead to a commensurate ebb in the incidence of catastrophic drift. All this makes a trout reasonably likely to feed on the surface, opportunity permitting.

So, regardless of the time of year, fish will be looking at the surface - it’s what they do. What we have to do is present them a fly that grabs their attention. At times where the water is impacted by colored light, color in the fly can be a big factor. I talked about this in an earlier post.

This is where the LaFontaine Double Wing really comes into its own. It becomes a bright spot on the surface, unencumbered by the clutter and camouflage of subsurface environments. In the window of the trout’s view of the surface a colorful Double Wing is like a beacon on a bleak horizon. A bright spot silhouetted against the sky or a distant landscape as opposed to something drifting in an environment like this with its mottled backdrop. Remember the trout is seeing this with a lot less acuity than you are. To the trout it’s all one big blur.

But the surface is unencumbered. All we need is to get the trout’s attention. Obviously the form is one thing. But we put some dents and dimples in the surface, which causes bright lights due to the lens effects I talked about earlier. We also add some sparkle with our materials. We add a stark wing that appears in the window of the trout and we present a form that may be representative of food. That’s what a fly like the double wing does.

The Antron tail adds sparkle due to the material and also indents the surface. The rear wing has the surface trail like a caddis wing. The palmered hackle provides the lenses one associates with surface tension, the white wing is an attention getter and the color matches the ambient light. You’ve checked all the boxes.

In other conditions certain other flies may work just as well, or even better than the Double Wing. I tie my caddis in the style of LaFontaine’s dancing caddis without the fancy hook. A body that rests on the surface, a wing that presses down on the water’s meniscus and hackle to produce the dimpling of the legs. All things that cause that sparkly outline we see from things floating on the surface.

I also took a page out of LaFontaine’s surface sparkle emerger and added it to a fully winged caddis. The sparkle from the Antron bubble does wonders on the surface. The wings add a certain silhouette, blurred as it may be. But all we’re looking to do is that as the trout rises, drawn by all the visual commotion of the sparkles and color, we’re looking to provide just a bit of verisimilitude to our offering. This does it very well. And of course it also does work in places where the trout are used to seeing caddis flies in one way or another.

A mayfly imitation, such as the vaunted Adam’s does the same thing. As do things like the Wulff series of flies, or the Humpies, or a million other attractors. The Madam X’s and PMXs with their bulk and wiggly rubber legs, or the Chernobly series all do the same thing, build something that gets the trout’s attention, ether by creating a flash on the surface, or putting one there by the use of material, give it something to stand out against the background and don’t worry too much about what it looks like - thr trout can’t tell.

Trout, especially browns are negatively phototropic. That’s a fancy way of describing their vampire like aversion to light. But as the shadows lengthen, and the light dims these fish will emerge to lie in the little runs and potholes that form the shoreline of any river.

Come down a river like this, as the light fades, and probe those seams along the shore or the mid river holes, and despite the snow clad slopes looking down at you those fish will rise up to your flies. I know, I’ve been there, I’ve done that, and I’ve caught those fish.