Fly Lines

The least talked about gizmo

There’s my fishing partner Frank showing immense ease with line control, not so much with fish catching. But we all have our crosses to bear. That’s one of the functions of a fly line - the ability to feed a fly to a fish, even after the cast has been made and the fly is on the water. Making that cast is of course another such function. A nice easy loop and a good cast is partly the angler, partly the rod and partly the thing that’s actually being cast - the line. The line is instrumental in taking your fly to the fish, allowing you to maintain control of that fly so it can actually be fed to a fish, and if not eaten allowing you to pick up the whole mess up and put it out there again.

And yet it never ceases to amaze me how little attention is paid to them, and how misunderstood they are, even by those who design and build them. Here’s a little discussion about the fly line.

First, as is my wont, the physics of the situation. When you cast a fly line (and that’s what you’re casting, the line, not the rod) you transfer energy and momentum to it. That energy is used to propel the line from its starting point to its end point. All of the energy imparted to the line is depleted in overcoming the drag felt on the line as it moves through the air.

Consider the forward cast. It starts at a backcast where the line is elevated and still (if it isn’t still when you start your forward cast you get that nasty sounding crack and often even break off your fly). At this stage the line has some potential energy due to its height above the ground (Potential energy is the energy you store in an object when you lift it against an applied force, in this case gravity). The kinetic energy (which is the energy stored in an object due to its motion) is zero because there is no motion. As you impel the line forward and get it moving you start storing kinetic energy in the line. As soon as the loop starts forming ahead of your rod tip you lose the ability to impart any more meaningful energy to the line. At this stage you’d be trying to push a rope - that doesn’t work.

As the fly line extends in front of the rod tip it unfurls in loop.

It doesn’t matter if you’re casting a two handed rod like my buddy Rick here or a single handed rod like Frank at the top of the article. The line still unfurls in a loop with the sections closer to the rod tip coming to rest and the upper section of the loop coiling out. As this happens the kinetic energy stored in the line is being depleted in overcoming the air friction (or drag) on the line. Every inch of line unfurling depletes more and more energy. However every incremental inch of line also needs to travel further. The kinetic energy of any object is given by the equation below

where m is the mass and V is the velocity. For a given amount of energy if you can make the mass lower the velocity goes up. One simple way to do this is to taper the line. As you march along the taper the mass of each segment of line goes down, which means if we impart a certain energy to the line, as it unfurls the line can maintain its speed. That’s one way a fly line helps you cast, and that’s one of the reasons for a taper on the fly line

There’s another trick line makers rely on. If you want to throw a string across a gap one way to do so would be to tie a stone to one end and then throw the stone. The same sort of concept can be used in a fly line. In fact that’s exactly what a shooting head is - a short, heavy piece of line attached to a finer running line. The angler basically slings the shooting head out there and it drags the running line out. In a less extreme way, that’s what weight forward lines do. They have a slug of weight up front that drags out the running line to allow you to get distance.

I love fishing medium sized trout rivers. These are the ones with flows somewhere around 1,500 to 3,000 cfs and a width around 100-200 ft. They’re more intimate than the bruiser 9-10,000 cfs rivers like the Missouri or the South Fork of the Snake but still have the characteristics of big rivers.

You can trundle down these rivers dragging a big nymph under a Thingamabobber through the deep trenches. You could also tie a 10 lb dumbbell to a fish hook, stick the fish hook in your lip and throw the dumbbell out the window. There’s about as much fun in either activity. On the other hand, if you fish these rivers correctly they readily cough up 50-150 fish days.

These rivers are the ones those heavy front-end weight forward lines are apparently constructed for. They are typically the worst thing for fishing those rivers. Bigger rivers like these hold most of their trout in a very small section of the river. Especially the trout that are readily catchable. There are always exceptions, but most of these fish will be in structure that is easier to survive in - gentler currents or more cover from the currents, a ready supply of food and some nearby cover.

This is the Colorado River below State Bridge. As one comes drifting down this section you find the fish along the left bank in the soft water before you go into the curve. A guide with the acumen of my friend Kevin will keep that boat in the middle of the river as you enter the fast water and the angler hits the soft water on the inside of the bend. Cast, drift, pick, cast drift and so on. Most times you should be into a fish right at the top of the soft stuff on river left. If not pick up and throw to the tail of that slick spot. Couple or three casts as you come around the bend and by the time you get to the first leaning telegraph pole on the railroad tracks on river right you want to flip over and hit the soft seam along that side. There’s a deepish trough there, where the water sloughs along, its speed broken by the large rocks that make the railroad embankment’s base. You cast ahead of you. Drift, pick, cast. Most of the time you have some sort of a dry on, even if it’s just the top of a dry dropper rig. But you need accuracy. Shooting line isn’t an option, you’ll just end up in the wrong place.

And you can’t lift running line. This is one of the shortcomings of those front end loaded lines. It’s easier to lift line that’s lighter the further you go from the rod tip. Which means you’d have to strip in line before the next cast. That swamps your dry, makes you waste time and inevitably puts the line in a spot where you have to jump though hoops to get it back to where it needs to be.

Here’s another spot, this one on the Roaring Fork part of the way between Carbondale and the Westbank ramp just outside Glenwood Springs. The river flattens out into a flat riffle about 200 feet wide and a half mile or longer

.The river bed is full of potholes ranging from washbasin to bathtub sized. They are slight depressions deep enough to hold the bigger fish. they appear as slightly darker, greener spots through the broken surface of the river. Depending on the time of year the rest of the river is shallow forcing you to fish a bit of a way away from the boat. As the guide takes the boat down the riffle meandering and slowing it down to keep you in productive water, you the angler, need to hit those pockets. I typically fish this section with a hefty Double Wing and 3 small tungsten bead head droppers.

You drop your flies a few feet above the pothole you’re trying to fish, throw a little upstream mend, do a little stack mend as the fly approaches the pothole. Let the mess drift though the pothole. If it’s one of the bigger ones you can hit it again a few feet away, or pick your line up, small pivot and drop it on the next target. You don’t have the time, nor should you have the energy to strip it in, shake the water off the dry, work the line back out to length and hit the next hole. All the while there are trout down there that need catching.

So now, not only do you need the controlled cast, but also a judicious mend or two. And that brings us to the next thing a fly line should help you do - mend. Mending line is an essential for fly fishermen. Watch an experienced angler at work and they’re subconsciously mending line almost constantly. Just doing it. A flick here, another one there and the flies do what they’re meant to do. One of the most delightful exhibitions of this is watching this young lady, Isla, give you an exemplary demonstration of how it’s done, just one little mend at exactly the right moment and she’s on.

Just like the situation when you cast a line, once you’ve started the mend there isn’t any more energy you can impart to the line. All the energy you’ve imparted must lift enough line off the water and propel it backwards to get you the mend you’re looking for. But once again as more line is moved more energy is depleted from you initial charge. Each successive bit of line must be easier to move. It must have less friction coming off the water and less mass that needs to be moved back. You can make small mends with anything. The issue becomes one of more import when the mends are larger. Now that constant taper of the fly line to the front starts mattering.

Many years ago we were doing a lot of testing up at INL outside Idaho Falls. I’d go fish the South Fork on the weekends and days off. While large sections of the South fork are heavily braided, there are sections, especially below Lorenzo where the river barrels past steep drop offs. The key to fishing this water seems to be to get your nymph down there and start mending, and mending.

If you want to fish this sort of water without your arm falling off, you really do need a line that mends easily over a wide range of casting distances.

It would seem that for casting, mending, line control and just about everything other than wildly lobbing a fly out into the deep blue yonder a fly line with a long front taper makes the most sense. Obviously a line you use of a stream such as this

could be very different from one being used on a river like this

But in either case that front taper with a consistently heavy section behind it makes most sense. Lines made for shooting are always better suited to cases where you can sling the line out with marginal need for accuracy and you don’t mind stripping a bunch in before your next cast. Even on big waters using big two handed rods you’ll find that if you want to control your swings and mend line the traditional Spey lines (or even a double taper as we used to use in days gone by) work wonders.

I still fish a lot of traditional long headed Spey lines for that sort of work.

They’re good for catching fish like this.

But this is not a story about two handed rods and lines. However, in there is the beginning of what has become my favorite sort of taper on a fly line. The story starts with Lee Wulff who would fish these little toothpicks for Salmon as all around him people wielded these huge 13-15 ft long weapons. Lee invented the triangle taper line, one that had a long front taper. In fact a variety of those triangle tapers are still available. My gripe was that they didn’t have a long enough front end by any standard.

They typically have a head length of between 36 and 40 ft, which is a lot better than most. The other problem, I thought was that even though they have the right idea the taper was a bit too extreme. It doesn’t let you build that reserve of energy and momentum a slightly heavier middle body would. So I continued fishing double tapers because at least they had some semblance of what we actually needed. The next line that came along was the Mastery VPT from Scientific Angler. Other than the Sharskin non-floating front end that needed constant attention, this line was getting there. It had a long front taper a bit of a belly and a Godawful white sharkskin front end that they later replaced with a smooth one.

It had a 35-40 ft front section which was better than anything else around and I fished a lot of them in the early 2010s on Sage One series rods. Still have those rods, they’re beauties.

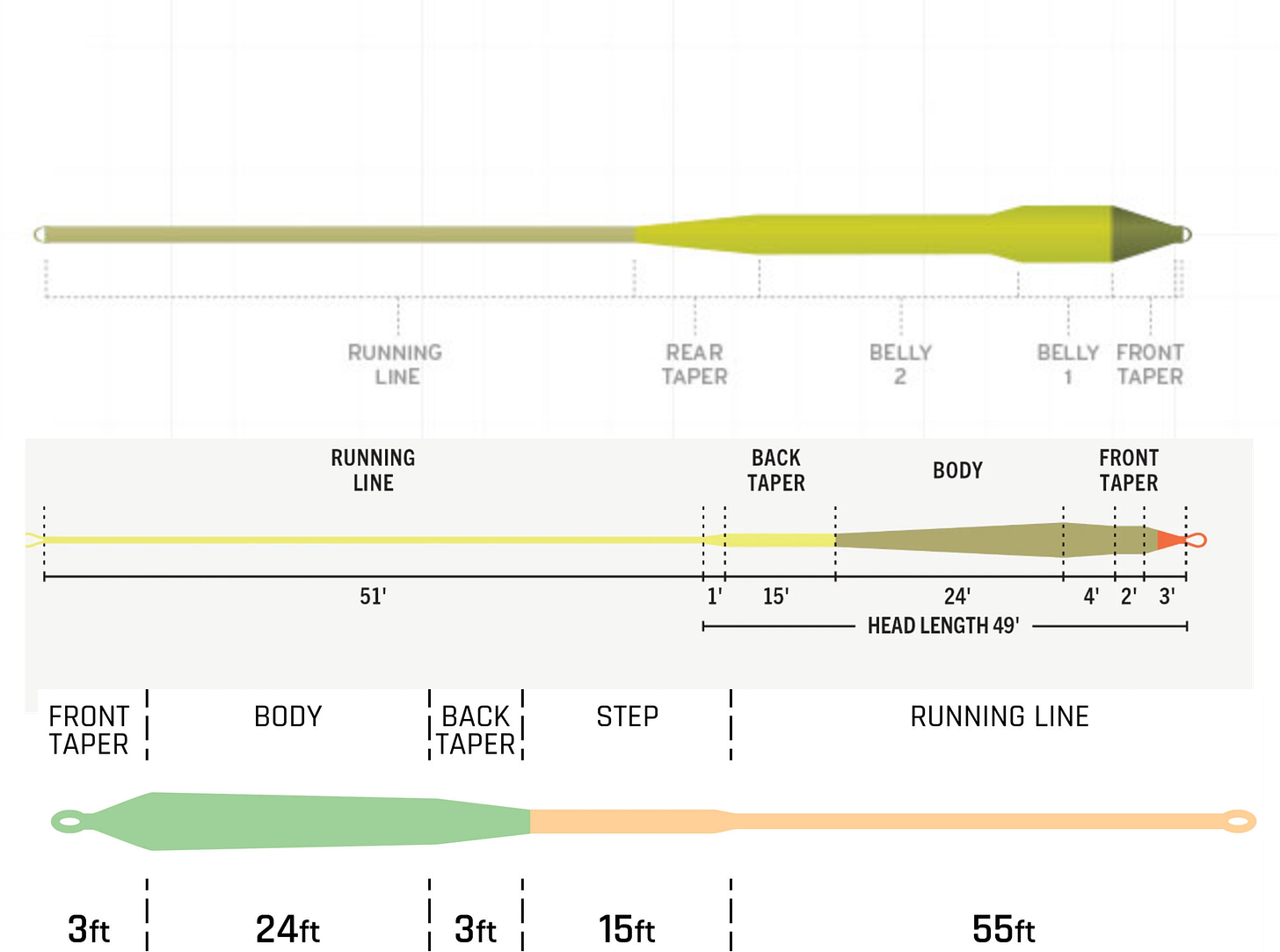

But then, like all good things, they stopped making the line. I snagged a few from here, there and the other, but that was it. The struggle to find a new line continued and I basically had to go back to fishing double tapers. This started the era of the rise of the bassackward, I don’t know what the heck I’m doing, it sounds like a good idea, maybe I should have listened in physics class, category of fly line designer. These are the guys that gave you this masterpiece of fly line design:

Since we need a heavier bit of line turning over a finer bit of line, lets put the heavier bit by the tip with a long back taper. You see that long back taper will help you mend the line, because it’s so much easier to lift a heavy bit of line by flicking a light piece of line. Momentum, kinetic energy, what’s that? These lines seem to have been designed by people who had their heads up their collective tuchus. There ought to be a law against this sort of numbskullery. And it looks like everyone went for it - lock, stock and barrel. And they’re still out there hawking this nonsense. That line above is from Scientific Anglers. Not to be outdone, Rio had to get into it too. Here’s their bit of nincompoopery.

And here’s AirFlo trying so hard to prove that fools seldom differ

But in this wilderness there is still some light and maybe sense will finally prevail. A few years ago Orvis put out their Pro Trout series of lines. Now here’s one that seems to have been thought out by someone who knows a thing or two. It’s strange how Orvis owns SA and yet SA seems to perpetuate its own brand of imbecility. The Orvis Pro Trout series, however seem to be hovering around the correct location. In fact I think they’ve done a reasonable job of getting the dimensions right.

With 40 some feet of belly and taper in the front they’ve got themselves into the right sweet spot. They have enough running line to let you feed line out to distant fish as we see Frank doing here. There was a whole pod of rising fish. I was rowing, Frank was showing me how the whole not catching fish thing is done.

As you try feed line out to fish feeding like that you now need heavier line pulling out lighter line. So there still is place for the running line. But it all depends on where you’re fishing, how close the fish will let you get to them and how long you can cast. I personally believe in getting a fly as close to the meaningful window as I can. The less the fly has to float the less the chances of a mistake. Others like shaking out bunches of line. Big Flats like this bring up tons of rising fish on rivers like the South Holston.

But often those fish won’t let you get close to them at all. Long cast, long drifts and a healthy pickup are the order of the day.

If you pull it off the fish aren’t half shabby either, like this one being held up by Matt Murphy, another one of those super guides I have the fortune to fish with.

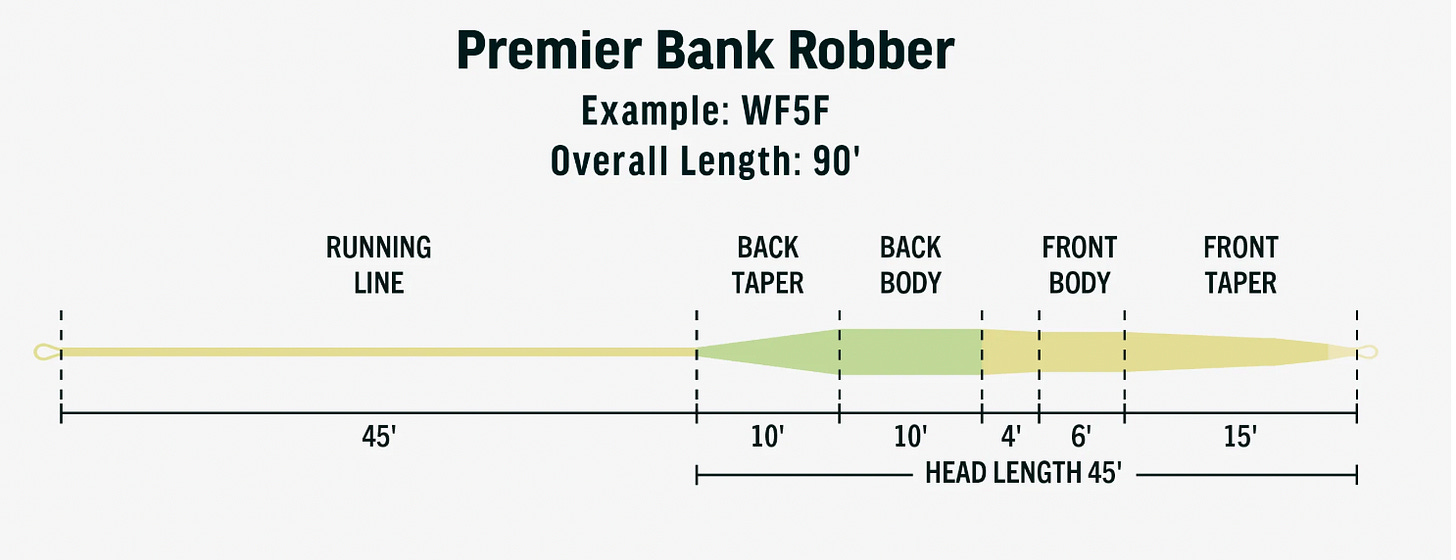

I found the whole Rio page about the line they call the the Bank Robber to be a bit of a hoot. The line itself is another one of the ones that comes close to being the right thing.

A little shorter on the business end than the Orvis one, but at least they have the right idea. The hilarity comes from their description of the line (or should I say their complete lack of perception as they wrote the description).

And I laugh because I have to ask, why is this a specialty line. You say it works for dry flies, dry dropper combinations and nymphs, it has a long taper for easy mends and drag free drifts (I’ll give them a pass on the “back taper” bit because it seems their designers don’t know their asses from anything else, so we’ll just let that go), it has a fine front taper for precise presentations. What else could you ask for in a fly line? Yet this is not their standard taper. It boggles the mind. Their standard multipurpose line is another one of those backwards tapered catastrophes.

I do like lines with long front tapers. Barring those my go to lines are double tapers. In fact there are a few situations in which I’d rather have a double taper. One, of course are the small streams I fish out East. A weight forward line makes little sense when you’re mostly casting 10 to 20 feet of fly line. Streams like this, even with peacocks observing the comings and goings.

The other place I like double tapers are big rivers where I need to pick up and throw long casts. There are rivers where for one reason or another you have to constantly pick up and throw long lines with quick casts. This is the Roaring Fork, and as you come down this stretch you want to hit the little pockets. It’s going to be a quick moving thing. Cast, drift a couple of feet, you either have a fish or you lift and hit the next pocket. Your guide has a chore getting the craft downriver without banging rocks and tossing you over board. He does that. You pick the place apart surgically. A double taper lets you do that. No stripping in of the running line needed.

The other are spots where the fish just won’t let you get close, like this river here.

You’re left with two choices - long drifts like Frank had going in the video above, or long accurate casts. I’ll take the long, accurate cast.

There are of course other types of lines, sink tips, sinking lines, etc. I don’t much fish them, so I really don’t have an opinion, except for Intermediate lines. I still consider them the best option for windy days. Their finer diameter offers a reduced wind resistance and makes for a great option. A light amount of floatant floats them, and you can clean them off by just pulling them through a folded piece of cloth.